Robert Mckee Story Workshop

May 1, 2016 / The Twelve Mysteries / storytelling

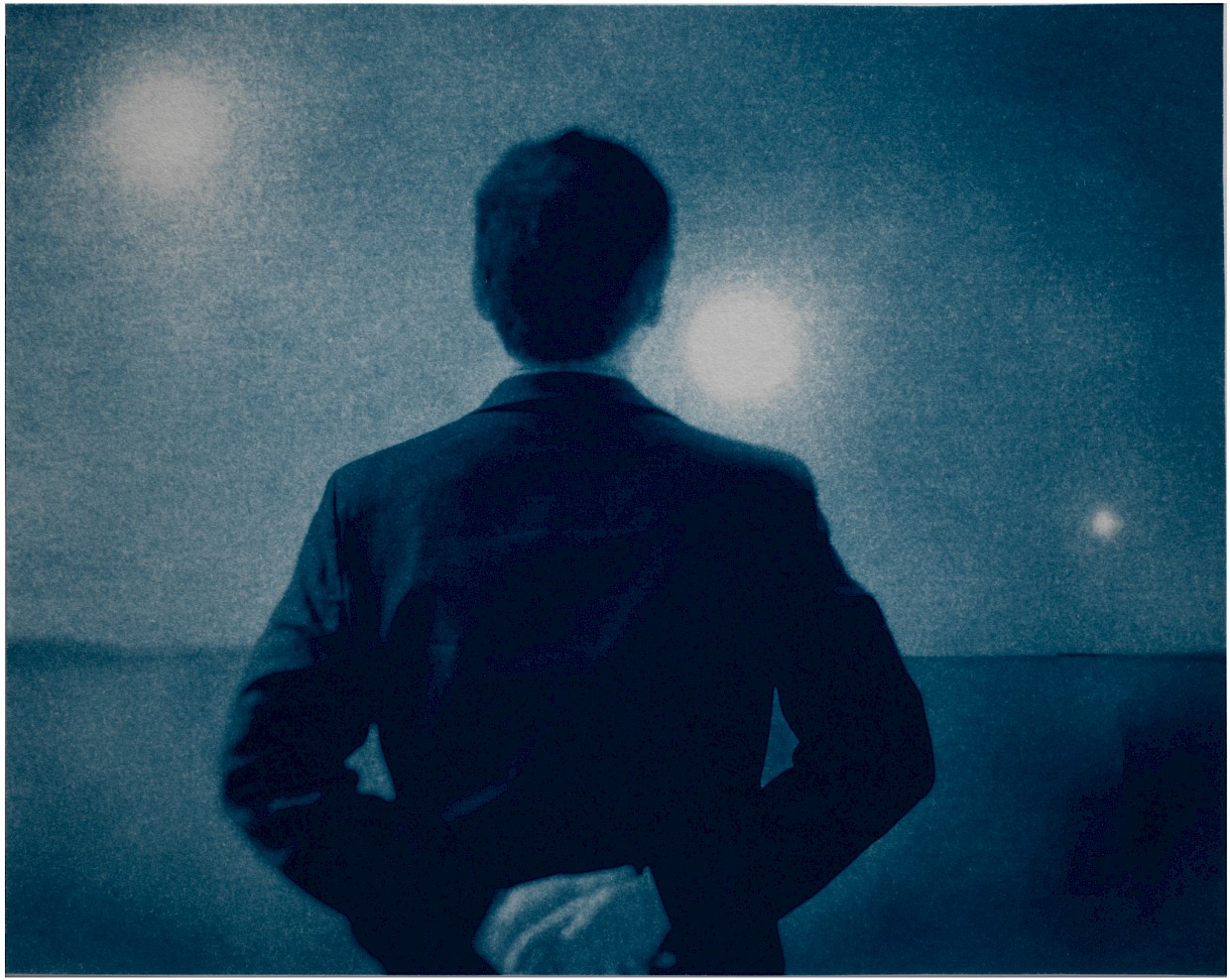

I just came back from Robert McKee’s Story Seminar held in New York City. McKee is well known in Hollywood as the Story Doctor. He teaches the structure of stories and how they work. While he focuses on movies, his teachings can be applied to all kinds of storytelling–including the wordless novel that I am attempting in A Million Suns. That is why I signed up; it’s part of my ongoing research. Up to this point (Parts I and II), I’ve been cobbling together an understanding of story structure. I decided that it was time to seek help and learn from an expert.

Taking this seminar was reaffirmed to me during fotofest. One portfolio reviewer commented that at one point in the story, “something bad” has to happen to the character. That’s part of storytellingäóîsomething has to happen to the character, or else there is no story. Instead, the photographs will be a portrait, a day in the life, where nothing bad happens. So I knew I was on the right track signing up for McKee’s Story seminar.

It surprises me to no end that I’m into this question - how can I apply the three-act story structure used in novels and movies and apply them to photographs? I’ve sometimes wondered why not abandon photography and be a writer instead. I’ve considered that, but I like the challenge of it. It’s a form of creative limitation. I’ve written about this before in this blog. My mentor once said that in creating art, setting limits are good, as those limits force the artist to push against those limits and see what is possible.

So Back to Story

When I say three act story structure, what I actually mean is what I posted above. It starts with exposition or set up, progressive complication, crisis, climax, and then resolution. This structure dates back thousands of years. One particular story structure referred to as the Hero’s Journey is embedded in the mythical stories from Homer’s Odyssey to George Lucas’ Star Wars. It really works. Why it works is an interesting question in itself. Recent cognitive studies show that our brains are actually wired for stories. That is why we love them and gravitate to them. It is how we understand the world. As Robert McKee says, “Storytelling is the most powerful way to put ideas into the world today.”

So what I’m trying to do in A Million Suns is to overlay this structure in a fine art photography project. There are many gaps that I need to fill in. Can it be done? Absolutely, woodcut artists in the early 20th century did it, like Lynd Ward, Otto Nuckel, and Frans Masereel. But I don’t think that is the real question. Rather, the real question is whether it can be done effectively in a fine art photography series where each image has to stand by itself. Or will it be a complete disaster. I guess I will find out once the whole project is done. If I fail, that’s okay. I will just try again in the next body of work.